A New Blue: Lapis Lazuli on The Silk Road

In the modern world where materials are available at the click of a button, we often take for granted the wide variety of blue pigments available to us. While we generously cover a canvas in ultramarine, cerulean, and cobalt, we can forget that it was not always so easy to access quality versions of these pigments. There was a time, particularly during the Middle Ages, where the introduction of lapis lazuli to the art world was both groundbreaking and frustrating, as it became available on the international market, accompanied by its many obstacles to acquisition.

‘The Silk Road’ is the term used to describe a collection of well-travelled trade routes that facilitated trade across Eurasia. By connecting the easternmost city of Chang’an in China (now known as Xi’an) to the westernmost points of Damascus in Syria and Constantinople of Byzantium (now Istanbul in Turkey), a variety of new products and materials were able to be exchanged between countries that lay on the route. Upon arriving in the more western areas, trade could continue across the Mediterranean Sea, reaching important port cities such as Venice, from which trade between European countries could flourish, aiding the Medieval European fascination with the aesthetic value of Arabic script, Persian rugs, Chinese porcelain, jade, and, importantly, lapis lazuli.

Lapis Lazuli

Image Credit: Gemological Institute of America

Lapis lazuli was particularly revolutionary among artisans of the Middle Ages. The stone displays a deep rich blue which, joined by its monetary value, made itself desirable in jewellery and therefore among jewellers. It was valued by artists of the time for similar reasons; the blue pigment that was able to be created by the stone boasted properties unattainable with other blue pigments available at the time, such as azurite. Blue made from lapis was not prone to oxidise, nor fade, maintaining a strong, beautiful blue for a much longer period.

Despite the utility of the stone and its introduction to the west, it was not easy to acquire. Most of the lapis present in Europe at the time was imported from Afghanistan, where it was difficult to find and difficult to mine, meaning there was a low supply for the high demand it possessed across Eurasia. As a result, it was high in value before even leaving its country of origin. The length of the journey it then had to take to Europe, and the risk merchants took by carrying it (bandits looking to steal expensive goods were not unheard of on the silk road), only served to increase its price further.

Once in the hands of an artist, undoubtedly commissioned by a person with high status and economic power, they began the laborious process of making it usable. in order to create a bright, clear blue, one had to crush the stone and separate the crystals from the mixture through several cycles of washing and decanting. The varying levels of success of this process explains the differing purity of lapis-based pigments (usually less striking in Greek or Roman pieces than their Asian contemporaries).

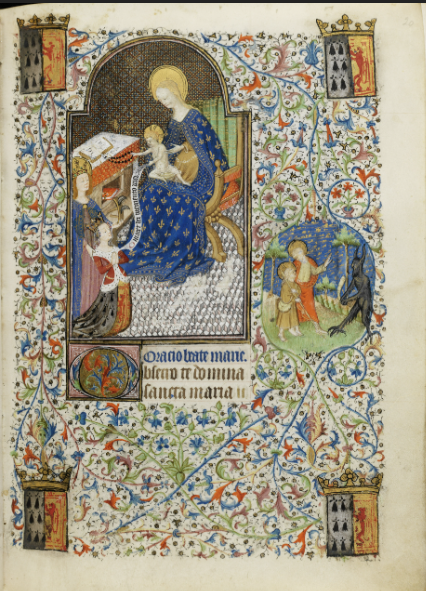

The Hours of Isabella Stuart (MS 62)

Image Credit: The Fitzwilliam Museum

Once the paint had been created, it did not spread easily, so the colour would usually be used in small parts of illuminated manuscripts or in a book of hours. Its use in these religious materials was most likely as an extra way for the wealthy to praise God, by spending high amounts of money on their dedications to him. The clarity of the blue would have been other worldly and almost unimaginable to a historical audience, and thus it only makes sense for it to be present in items representing the celestial.

Lapis’ existence in art from the Middle Ages is rare and valuable. It was not easy to obtain nor to use, yet the strength of the blue it created made it worth the hefty price tag it came with (to those who could afford it). Its rarity would have only assisted the transcendental connotations it came to have, and increase the feelings of privilege one would experience while looking at it. So while it may have been unfortunate to artisans at the time that it was not more readily available, nor easy to paint with, it is that which made it so valuable then and so impressive now.

Sources

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Silk Road." Encyclopedia Britannica, July 31, 2024.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Silk-Road-trade-route.

"The Silk Road". National Geographic Society. 26 July 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

Pastoureau, Michel. Blue : The History of a Color / Michel Pastoureau. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2023. Web.

Valuable Secrets in Arts and Trades OR, Approved Directions from the Best Artists. Containing, Upwards of One Thousand Approved Receipts. For The Various Methods Of Engraving on Brass, Copper, or Steel. Of the Composition of Metals Of the Composition of Varnishes Of Mastich, Cements, Sealing-Wax, &c. &c. Of the Glass Manufactory, Various Imitations of Precious Stones, and French Paste Of Colours and Painting, Useful for Carriage Painters Of Painting on Paper Of Compositions for Limners Of Transparent Colours Colours to Dye Skins or Gloves To Colour or Varnish Copperplate Prints. Of Painting on Glass Of Colours of All Sorts for Oil, Water, and Crayons Of Preparing the Lapis Lazuli, to Make Ultramarine Of the Art of Gilding The Art of Dying Wood, Bones, &c. The Art of Casting in Moulds Of Making Useful Sorts of Ink. The Art of Making Wines Of the Composition of Vinegars Of Liquors, Essential Oils, &c. Of the Confectionary Business. The Art of Preparing Snuffs, &c. Of Taking out Spots and Stains. Art of Fishing, Bird-Catching, &c. And Other Subjects, Curious, Entertaining, and Useful. A new edition improved. London: printed for J. Barker, dramatic Repository Great Russell-Street, Covent-Garden, and J. Scatcherd, Ave-Maria Lane, 1800.

Images

https://science.howstuffworks.com/environmental/earth/geology/lapis-lazuli.htm

https://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/illuminated/manuscript/discover/the-hours-of-isabella-stuart/folio/folio-20r-211

Cover Image

Lapis lazuli Rock, Gemological Institute of America via How Stuff Works