Graphite Grey

Shades of grey plague us. A grey sky: foreboding. A grey stretch of road cutting through fields: a blemish. A grey lake: probably freezing—with respect to ‘synaesthesia’ (the sensory effect a colour has on a person). Physical grey is thus less than inviting. Linguistically? Well, grey has been co-opted as little more than an in-between. ‘Shades of grey’ – i.e., in reference to morals or justice, suggest multiplicity or confusion.

Whilst this article respects how grey inhabits the in-between regarding colour theory, it is less interested in reiterating grey’s connotations of boredom or drudgery. Grey, like any other colour, occupies an important space in our universe. Colour theorist David Batchelor describes within his book The Luminous and the Grey the dependence of luminous colour on grey to portray its own brilliance (2014: 61). This is one of grey’s powers as a colour tool, the power to complement. His description of how colours ‘complement’ in colour theory also lends itself to metaphor when considering just one shade alone: graphite grey and its practical applications and capacity for potential.

Now to consider this article’s important epithet, and the significance of graphite grey. If you have ever scribbled with a pencil, this title might conjure up a particular shade and maybe even that unmistakable scent of discarded shavings or the school-day recollections of a shadowed colour smeared down the resting edge of your hand.

This article begins with graphite, but will end with potential.

Graphite

Sample Image from Mindat.org

What is Graphite?

Like diamond, graphite is made of carbon. However, graphite’s molecular structure makes it very different from its sparkling kin.

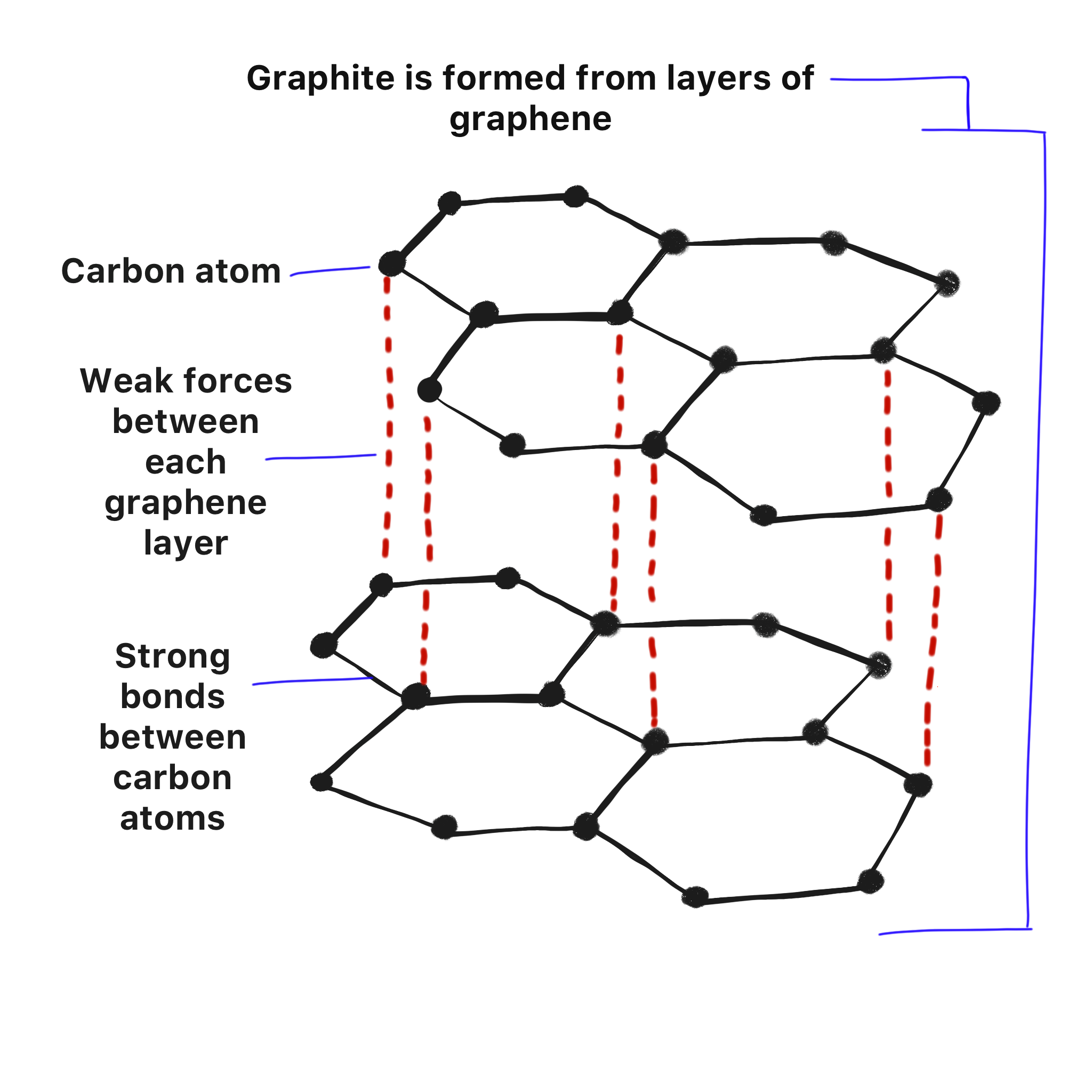

Unlike diamond, graphite is softer, dark grey coloured, and unlikely to find itself onto a piece of jewellery. The colour and durability of materials are decided by their molecular structure. Whilst the atoms of carbon that make up diamonds form four strong bonds, atoms that make up graphite only form three. In doing so, this creates a structure called ‘graphene’, and only when layers of graphene are stacked together are they called ‘graphite’. Unlike the strong bonds that are found between the carbons within graphene, there are only weak forces between each graphene layer. This means that these layers can be easily separated or can slide over one another. This slippery property allows graphite to, in certain contexts, be used as a lubricant (more on that in Colour of Wealth). It’s also what gives pencils the ability to leave a mark when they are dragged across a surface.

Structure of Graphite

Illustration by Amy Nugent

The reason why these marks show up grey, and why graphite isn’t transparent in the first place, is because its molecular structure causes it to absorb light, in turn, making our eyes perceive it as a dark grey colour.

However, graphite’s dark grey is also cause for its misidentification. Thinking back to the anatomy of a pencil, what are you likely to call its sharpened core – the pencil’s graphite, or the pencil’s lead? Although pencils had been in use for hundreds of years prior, according to Derwent Pencil Museum it was only after 1789 that they were no longer considered lead pencils due to the identification given by German chemist A. G. Werner. Ambiguity, grey’s linguistic trait, had played out quite spectacularly due to the similar look of both graphite and lead ore.

Colour of Wealth

Colours have long been intertwined with cultural signifiers of wealth, so much so that there have even been laws in place to control what colour you wear.

Whether it’s the colour of your expensive dress, the gold gilding your house, or which jewels you can afford to be decked out in, if there’s one colour that has historically seemed far from making this statement of stereotypical lavish luxury, it’s probably grey. Why might this be? Perhaps as grey is ubiquitous in less valuable materials, like stone, or occurs constantly within nature from land and water, to the creatures living there, to the ever-shifting sky.

Graphite grey would change this. Derwent Pencil Museum cites that in 1650 graphite became more valuable than gold. This was due to those slippery properties that were discussed in What is Graphite?, which facilitated its use as cannon lubricant in the 17th century and made it a highly valuable resource. Although its aesthetic appeal is unnecessary to this function, graphite grey’s niche characteristics significantly defy those stereotypes of drudgery.

Colour Tool

Today, graphite grey permeates society, although not so much for its cannon connotations. As a colour, its neutral tone is favoured by minimalist and brutalist designers. Furthermore, the 21st century tech boom increasingly perpetuates metallic grey shades through the nuanced hues offered by manufacturers. This preference may imply that grey is a fashionable staple of modernity, as it is clearly a huge part of our material landscape from gadgets: phone or car, to clothes, to infrastructure.

Illustration by Amy Nugent

But graphite’s grey isn’t just an aesthetic, it’s a tool. With respect to the pencil, it’s a relatively accessible one at that.

Today, graphite sits on our desk unassumingly, processed and packaged recognisably into a pencil. The pencil is a colour tool. Arguably, graphite is one of the most important colour tools in modern usage. Derwent Pencil Museum says that pencils have been circulating as writing implements since the fifteenth century. Unlike ink, writing with a pencil takes no time to dry, and unlike charcoals, is far less prone to smudging, in part because of the clay mixture that is added to the graphite of a pencil’s core to increase its durability.

It’s therefore no wonder that pencils are one of the first tools that find their way into the hands of children; they are instrumental in supporting literacy and learning, developing fine-motor skills, and form one of the most popular introductions to art through drawing. Whilst Batchelor examines grey’s differences from other colours, as ‘Grey can effect a neutrality other colours could only dream of’ (2014: 76), surely the cultural significance of grey’s educational usage depicts that this neutrality enables grey to inspire the most potential, too?

To consider the affirmation of this question, please allow a brief diversion to a man who was very passionate about colour. Josef Albers, famous abstract painter and educator, investigated colour through his creative practice and teachings. An iconic and recurring feature of his artwork was his use of coloured squares within squares to create a journey between complementary and contrasting colours. In ‘Josef Albers: The Magic of Color | ART + COLOR’ (2023), a video documentary directed by Sean Yetter, a recording of Albers’s voice sounds over a clip depicting his process of creation and he states ‘that art is not an object, but art is an experience’. From its structure, to its history, to its potential as a tool, graphite grey is more than an object as well, it is something that provides the experience of creation.

Shades of grey are everywhere. In our exercise books: a development. In our artwork, an expression. Batchelor asks:

‘If grey is so ordinary, so dull, so cold, so slow and so boring, doesn’t that make it quite unique among colours and thus, in its way, rather extraordinary? Wasn’t grey alone able to stand for every other colour in, for example, early films and photographs? And doesn’t it still, when asked to?’ (2014: 73).

Grey evidently opposes its criticism time and time again, and through colour theory and graphite we can see how this colour is not necessarily a deficit.

Instead, grey is a colour that exudes potential.

Sources

Batchelor, David. 2014. The Luminous and the Grey (Reaktion Books)

Derwent Pencil Museum

Josef Albers: The Magic of Color | ART+COLOR’, dir. by Sean Yetter, David Zwirner, 21 July 2023 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l3xpTtn7zo8> [accessed 10 September 2024]

Images

Graphite Sample Image from Mindat.org / Graphite: Mineral information, data and localities. (mindat.org)

Illustrations by Amy Nugent